Cedars in the Pines

Moise Khayrallah was troubled. In the wake of the September 11 tragedy, the image many Americans had of Arabs — including his community, the Lebanese — was one of conflict, violence and terrorism. After more than 120 years of being an integral part of the history and life of North Carolina, seemingly overnight Lebanese-Americans had become outsiders again.

Moise Khayrallah was troubled. In the wake of the September 11 tragedy, the image many Americans had of Arabs — including his community, the Lebanese — was one of conflict, violence and terrorism. After more than 120 years of being an integral part of the history and life of North Carolina, seemingly overnight Lebanese-Americans had become outsiders again.

Khayrallah, a pharmaceutical executive, came to the United States from Lebanon in 1983 with his wife, Vera. Committed to preserving the area’s Lebanese culture and heritage, he wanted to find a way to capture the history of his people and share it with others. When Khayrallah was introduced to Akram Khater, professor of Middle Eastern history at NC State, he shared his ideas about educating North Carolinians about Lebanese-Americans.

With the help of Khayrallah’s generous gift, the Khayrallah Program for Lebanese-American Studies launched in fall 2010 to research, document, preserve and publicize the story of Lebanese-Americans in North Carolina and to educate the public on their contributions to the state. As part of the project, a team at NC State is creating these educational tools:

• a documentary, “Cedars in the Pines,” on the history of the community that will air on UNC-TV;

• a traveling museum exhibit;

• a resource book and lesson plans for K-12 educators to teach the history of Lebanese-Americans in our state; and

• an online archive housing the personal stories, letters, photos, home movies and newspaper clippings of the state’s Lebanese-Americans.

“The story of Lebanese-Americans, like that of many immigrants, is one of hard work that led to success for themselves and their families and innumerable economic and cultural contributions to North Carolina,” Khater explains. “Today, there are about 16,000 first-, second- or third-generation immigrants in our state, largely concentrated in the Triangle and Charlotte. Early immigrants were more concentrated in eastern North Carolina — along what is now the I-95 corridor — as they made their way from Ellis Island down south.”

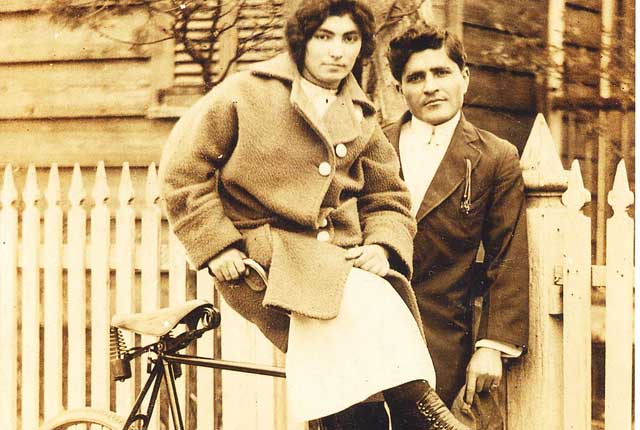

The first wave of immigrants, who came to North Carolina between the 1880s and the 1920s, settled in such towns as New Bern, Goldsboro, Wilson and Wilmington — right off the train tracks throughout the state. Nearly all of them “peddled” to earn a living, carrying suitcases filled with knickknacks like lace, buttons, needles and napkins — items one would find in a city store but that weren’t easily accessible to people living in small towns and on isolated farms across the state.

“They became salesmen offering products and services that small towns and farmers didn’t have, but also a real link to the community, bringing news and gossip from the larger cities,” Khater says. “They worked very hard to be a part of the local communities — joining Boy Scouts, sports teams, community groups and more — and have continued to integrate themselves into the community to this day, enriching it with festivals, celebrations, restaurants, culture and religions, their talents and entrepreneurial spirit.”

Khater and a team of public history graduate students are working to interview immigrants and collect and digitize maps, images, newspaper clippings and more to help tell the story of a group of people that many feel have long been invisible to the great majority of North Carolinians.

“We started capturing the voices of this community through oral histories, in part because there came a point when we exhausted the resources of libraries, historical societies and archives,” explains Caroline Muglia, a graduate student working on the project. “The truth is that Lebanese families in North Carolina have collected the richest history of the community to date. They lived the history.”

Muglia says that returning the project to the community “has been the goal all along. We are building a platform for the narratives of these people to continue to evolve and serve as an educational tool in the process.”

Akram Khater agrees, and he emphasizes his gratitude for Moise Khayrallah’s generosity. “Without his foresight and philanthropy, we would not have been able to take on the project,” Khater says. “Much of this oral history, these important stories, might have been lost — and with them, we would have lost an important part of North Carolina’s history.”

by Caroline Barnhill

This article first appeared in the college’s 2012 print magazine Accolades.