It’s Never too Late to Study Abroad: Turkey Part III

CHASS Dean Jeff Braden is traveling in Turkey as part of a delegation from North Carolina’s Divan Center, a nonprofit committed to promoting cultural understanding between the United States and Turkey. He is sharing his experiences and perspectives through a series of blog posts.

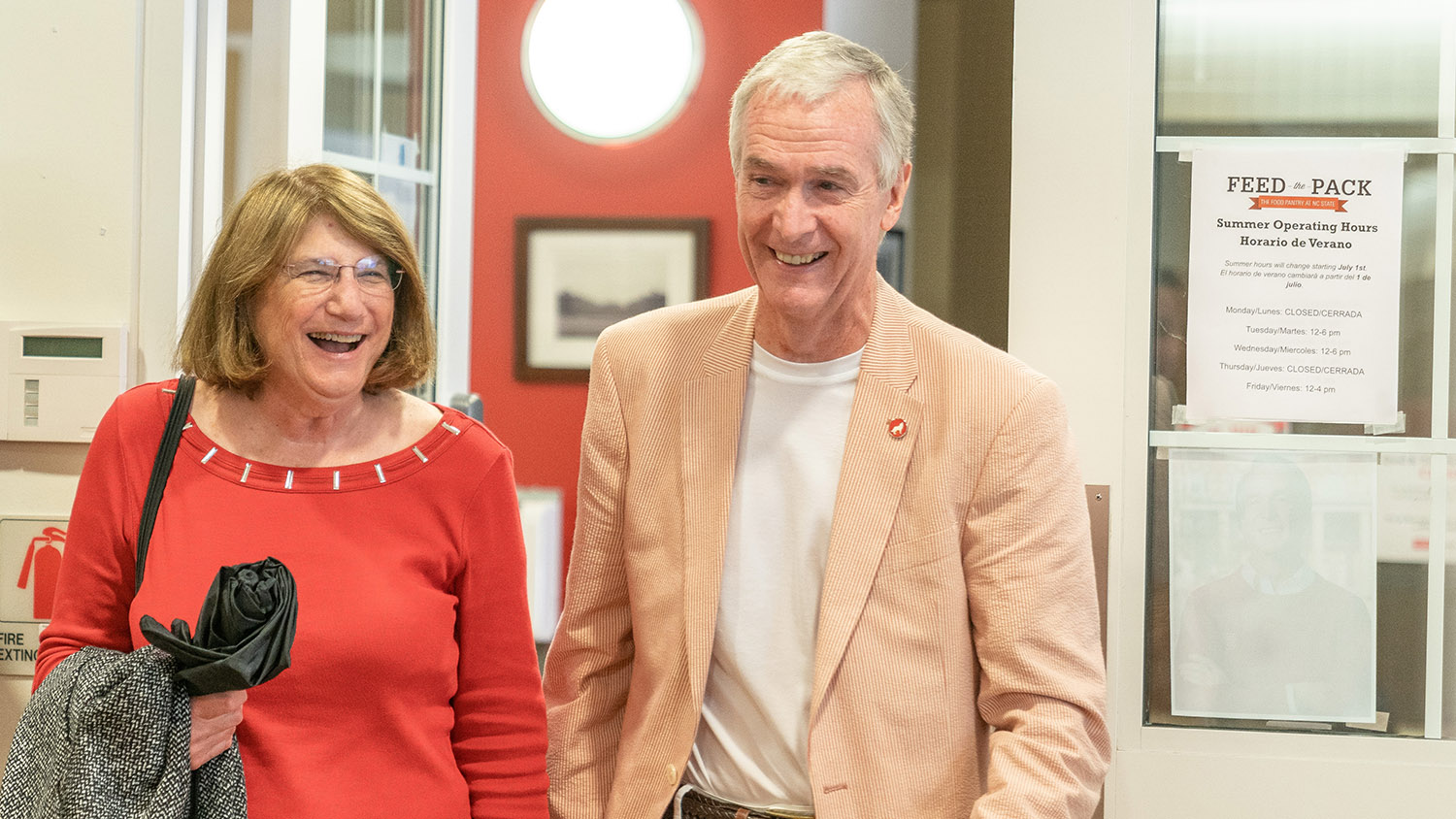

7:40 am Bus to Kayseri Airport, 4 July. Jill and I have wanted to visit Cappadoccia since some friends told us about its eerie landscape and rich history. Tales of surreal landscapes, multi-story underground villages, and religious sects and their leaders had only made us want to visit Cappadoccia more and more with each passing year. So the expectations were pretty high when we finally found ourselves seeing Cappadoccia for the first time.

It did not disappoint. As we came closer to the area, we began to see the pinnacles formed by the unusual layering of hard volcanic rock spilled out over a deep layer of compacted volcanic ash. The odd juxtaposition of these two layers created spires in which a hard boulder or rock would protect the softer ash beneath it from erosion, while the surrounding material was swept away by rain and wind. As a result, tall pinnacles of ash with black rock tops were created in oddly curved and rounded shapes. The surreal ecosystem proved surprisingly fertile, and so became home to a variety of peoples who dug dwellings out of the soft ash cliffs. As the area became the object of military conquest by successive rulers, the residents added deep underground villages to which their dwellings were connected by tunnels that would allow them to escape below and defend themselves. The strategic fortifications were tailor made for the Christian groups who sought refuge from Roman persecution, and later provided refuge when their form of Christianity (championed by St. Basil) was rejected by the Christian Roman emperor. For centuries, they carved churches from the soft ash and laboriously painted their ceilings and walls with religious images and icons. In short, it was rich in topography, history, and art–and was a bucket list item Jill and I were finally checking off.

Our tour began in one of the larger underground villages, a winding maze spanning four underground stories. We took the stairs to the first level, which was used as a stable during times of attack, in part because of the fact animals could not be coaxed further underground, and in part because of the smell and mess they’d make further inside. We then began the fascinating exploration of the underground warren, complete with small rooms for living, worshipping, storing wine and food, and traps to catch and foil invaders. When the tour guide shared that the lowest levels of the complex were the newest, it seemed incongruous at first, but upon reflection, made sense. When she brought us to one room and said “Notice the space for the plasma TV,” we all laughed. Perhaps this was the original man-cave?

After lunch, we visited a rug making cooperative where we were shown how Turkish rugs were made. I had seen the silk extraction process on my last visit to China, but found myself ambivalent as I watched the (exclusively) female weavers ply their craft. On the one hand, this cooperative allowed them to work from home and get directly compensated for their work; on the other hand, the repetitive motion of the stitching, the hunched posture, and the fine detail work made chronic demands on the body that lead to vision loss and back problems. The “explanation” and “display” of the various types of rugs was an unabashed sales presentation thinly disguised as an educational experience; we all laughed together at the charade. We finally departed for the open air museum containing a handful of Cappadoccia’s churches and museums (the artifacts of this site, and most others we visited on the trip, had been removed and were on display in Ankara). After a brief intro, we were off to explore the fascinating topography and history of the area.

As I said before, it did not disappoint. The Seuss-like structures wove in and out of the natural landscape, at times making it difficult to discriminate that which was hand made from that crafted by nature. The paintings on the ceilings were real in a way that invited one to feel a tie to those who had painted them centuries before (most of the churches were built and painted between the 9th and 12th centuries). In addition to the churches, there were kitchens, dining areas (where tables and benches had been carved into the solid rock walls; one table was so long it was rumored to seat

50 people), ovens, and more. We went wild taking pictures and exploring the area; so much so that the park employees finally chased us out and closed and locked the doors behind us. We were exhausted but buoyed on the one-hour drive to Kayseri, as we marveled at what we’d learned of the history and landscape (and anticipated yet another humongous meal awaiting at the hotel).

I was up early the next morning (Wednesday) and went for a run around Kayseri. It is at the foot of Turkey’s second-highest mountain on a dusty and arid plain. Unlike Istanbul, virtually all of the areas through which I passed were modern, with the exception of a few mosques and the exterior walls of the castle and city walls built in the

11th century. However, the city is ancient; at the very summit of Eerciyes Mountain, a Hittite tablet was found, verifying the mountain had been an object of worship many millennia before modern times. One of the things I like best about running is the odd, unexpected glimpses I get into the lives of those in the city through which I’m passing. This morning was no exception; shortly after I set out, I was passing through a small park and saw a young woman in form-fitting spandex workout shorts with a sleeveless tank top leading about a dozen other women in a dance/exercise class to techno dance music booming through her portable speaker as she shouted encouragement into her cordless headset. What made the scene unique for me is that all of the women moving to her commands were dressed head to toe in black chadors, whose running shoes poked out from underneath their hems. A little further down, I saw other similarly dressed women on outdoor elliptical equipment (two free-moving pipes in which you put your feet on one end while swinging back and forth holding the top of the pipes in your hands). A mile or two later I entered a second small park, and saw what appeared to be exactly the same class as if they had been magically transported there ahead of me. However, I couldn’t find the big park to which I’d planned to go; I finally realized I couldn’t find it because it had been replaced by a mega-mall and a nearly completed high rise. The price of progress, no doubt, but it was a shame to lose what little remained of the city’s green space.

Our group formed up and departed for a visit to a private school that is sponsored by the Hizmet movement. The school was quite new and very attractive, with children out playing on the composite playground surface as we arrived. We were struck by the sound used to let the children know that recess was over; rather than the sound of a jarring bell, music (to the tune of do-ray-mi) played, followed by an exceptionally calm and friendly voice beginning with “Dear students; the time for your recess has now come to an end. Please make your way to your classrooms to prepare for your lessons.” While we we laughing and remarking about how wonderful that was in contrast to what we typically experienced, we heard Turkish music, followed by the same voice in perfect and utterly mellow English announcing “Dear Teachers; your students are in your classrooms and eagerly waiting for you to arrive.” Needless to say, we were taken with the place before we even entered.

During our visit, we learned that the students in school were enrolled in an intensive summer English program, and the usual nine-week program had been shortened to five (and increased to 6 eight-hour days per week) because of the upcoming Ramadan. Just last year, Turkish schools had been reorganized into a 4/4/4 system; 4 years of primary school, 4 of middle school, and 4 of high school. They explained that, in addition to the intensive summer program we were visiting, students learned English throughout the year. We visited two classrooms of mostly 12-year olds, and quickly realized they knew much more English than we knew Turkish. It was fun–and left me with the odd feeling that I could converse more readily with the students than the officials who lead our two school visits (both of whom relied on Serdar, our group leader, to interpret). The schools creatively displayed English words and phrases between steps leading to different floors, and there were many professional quality posters in English and in Turkish with various messages to the students. On the one hand, I was impressed with how clean, orderly, and sleek the schools appeared next to those I was used to visiting in the States; on the other hand, I didn’t see any student work or teacher-made displays in the hallways, which gave me an oddly sanitary feeling, as if it was more like an office building than a school. Finally, we were told the school had been the vision of a man who had a modest business making and selling windows; through his commitment and will, he eventually put together enough money to build the school. The story reminded me of the scenes we’d seen the day before, in which the murals in some of the Cappadoccia churches displayed the patron of the church in the fresco (often as a child or onlooker in the depicted biblical scene); I asked whether this tradition of patronage had been well established in the area and continued on today. Serdar shook his head and replied that sadly the tradition had been lost, but the Hizmet movement (and others) were seeking to restore it. We left the school buoyed by our interactions with the teachers and students, and piled in the bus to head for lunch at Meliksah University.

Our first stop was the Rector’s (President’s) office–a man who was utterly charming, friendly, and still feeling his way about, having shared with us that he had been Rector all of nine days! Others offered their congratulations, but when it got to me, I said “Perhaps condolences are in order?” He laughed heartily; his candid, just-folks humor and bonhomie reminded me of our own Chancellor Woodson. When I asked him what he hoped would distinguish his university from (nearly-free) public and other private universities, he replied that he was hoping to shift the focus of the five-year old private institution from one emphasizing teaching to one known for its research, projects, grants, and graduate education. We bonded over the dilemma and challenges in achieving this goal, as I had struggled within our college and campus to maintain our strong commitment to undergraduate instruction while at the same time building our research, scholarship, and graduate education. We had the inevitable huge and utterly delicious lunch (this time Jill and I insisted on sharing a plate–and yes, for the record, I did have a little bit to eat, as I couldn’t insult our hosts!) that lasted nearly two hours. We were joined by a half-dozen assistant professors (all but one of whom was from the business school), and I sat next to the dean of the business school and commiserated over the decanal life (e.g., “What do a dean and the caretaker at a cemetery have in common? A–They both have a lot of people under them, and none of them listen”). However, I realized that even in our lean budget times, our circumstances were quite different: He had 1,000 students and 18 tenure line faculty (he was the sole Professor; he had three associates, and the rest were assistants), and only 8 other people working in the college. In other ways, however, they were better-resourced than we were; the sole psychology professor who joined us explained he’d welcome our faculty to come and teach (in English) for terms ranging from 1 month to 2 years, and they’d provide all travel, accommodations, and a $6,000/month stipend. In short, they were desperate for intellectual talent to help them build their university, and I filed that information away for my upcoming scholarly reassignment (whenever that happens!). I was touched, however, with the final scene of our visit. As I walked back with the Rector to his office, a young girl of about 10 years ran out and threw her arms around is legs. He beamed, unnecessarily explained that the young lady was his daughter, and thanked me for visiting. He immediately turned and walked away holding his daughter’s hand. I was impressed; he’d seemed to have unlimited time to visit with us, but the guy had his priorities down straight. When his daughter showed up, we were done. Good call!

We spent the rest of the afternoon/early evening taking the cable car halfway up to the top of Mount Erciyes and visiting an Armenian church. The visits showed us a modern, economic face to the region (we toured a ski area at about 9,000 feet elevation–well below the summit–that had been designed by Austrian engineers). The Armenian church provided a stark contrast, as it was an old building that was kept by a sole caretaker who lived on the premises, and served to maintain the building for the three remaining Armenian Christians living in Kayseri. The building and its caretaker spoke of the history of religious tolerance in which Turks take great pride, but it also suggested how migration and economic opportunity move populations and their associated traditions. As we were leaving, our guide hailed some local folks and explained that we were from the United States. They lit up and excitedly invited me over to have their picture taken with me. I was tickled when the woman to my right suddenly threw her arm around me just before the picture was snapped; it was a wonderfully genuine and spontaneous display of welcome that I find unparalleled in my travels.

We ended the evening by sharing dinner with three young couples who acted as local hosts and representatives of the Hizmet movement. It was a lovely dinner; I spent most of the evening chatting with the young couple (he is a civil engineer; she an architect, together they have a two-year-old daughter). Later, the husband of the couple invited us to his parents’ house, for which his wife was the architect. It was a stunning home in its dimensions and design; I was bowled over, and learned that the domicile was home to three families (his parents, his aunt, and his cousin’s family). It was about 1,000 feet above the city plain with a spectacular view; in any place, it would be a home speaking of wealth. That impression was confirmed when we left through the front door; it was a massive, thick steel door more like the door to a bank vault than a home. However, the generosity and hospitality of our hosts once again left us feeling blessed to be on the trip, and spoke to the universal values of friendship and kindness across cultures. When we returned to the hotel near midnight, the reality that we needed to be ready to leave early the next morning slowly sank in, but in no way diminished the pleasant memories of the food and friends we enjoyed that evening.

All for now….

Jeff

- Categories: