Language, Gender and Disney Princesses

With billions of dollars in box office and retail sales, the films in Disney’s Princess collection have an immense reach. The names that often define the movies are some of the most well-known fictional characters around the world — Cinderella, Snow White, Pocahontas, Elsa.

The films are produced for entertainment — and they’re entertaining. However, their messages can also be influential in how children, a core audience, learn about social norms and behaviors. NC State graduate student Karen Eisenhauer studies how language in the Disney Princess movies can depict and represent gender roles.

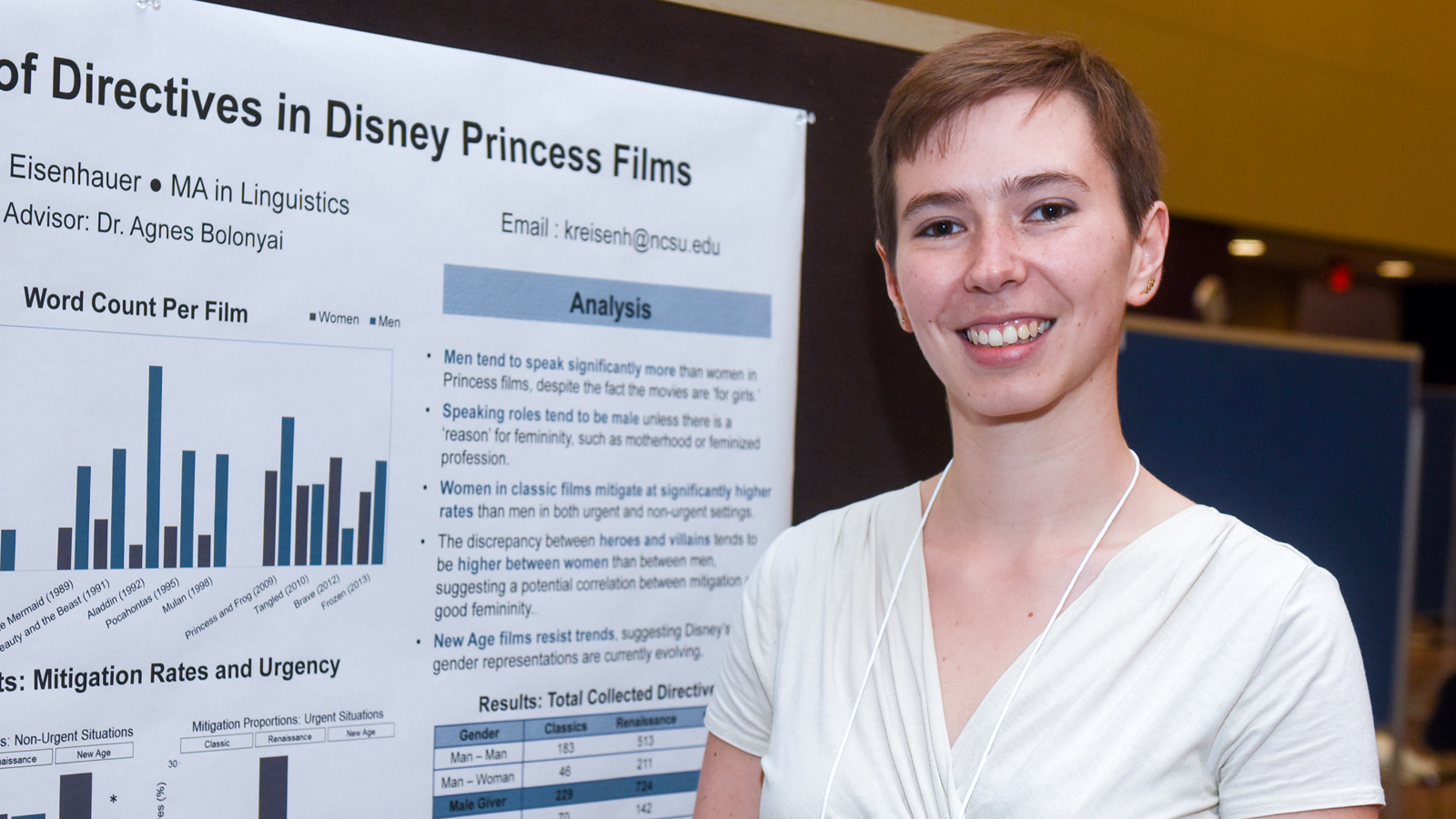

Eisenhauer, who will earn her master’s degree in linguistics in May, recently presented some of her latest research at the NC State Graduate Student Research Symposium. Her poster, “Directives in Disney and Pixar Movies: A Quantitative Analysis,” won first place in the humanities category.

We caught up with Eisenhauer, whose work with Pitzer College professor Carmen Fought has also been featured in the Washington Post and National Geographic, about her study.

What did you study?

Over 50 years of language and gender research, linguists learned that one of the main ways we communicate our gender identity is through language. Through careful analysis, we can actually quantify some of the differences in the ways men and women speak in specific contexts. We’ve established that masculinity is associated with qualities like commands, “tough talk” and conversational dominance, whereas femininity tends to be associated with mitigation, suggestion and collaboration.

Most of these associations are patterns we learn through interaction with others. But widely circulated cultural artifacts — like Disney movies — are also important tools to represent gender norms and expectations to us when we’re young. The Disney Princess movies are particularly infamous for representing narrow versions of femininity to young girls. A lot of people recognize the power of princesses, but few have attempted to quantify exactly what kind of message they are sending to children. Studies tend to be interested in how princesses look and act; but how they talk is arguably just as important for the gender roles they represent.

My research fills this gap by applying language and gender methodology to the princess movies. I gathered scripts for the 12 canon princess films, and now I test those for presence of the kinds of speech that have been associated with gendered performance in previous linguistic literature. Examples of these kinds of speech include compliments, apologies, questions and directives.

How did you analyze the language you observed in the various films? What were some of the things you looked for?

This specific study was an analysis of directives. Directives are defined as a speech act wherein the speaker tries to get their listener to carry out, or to refrain from, some action (e.g. “Pass the salt.”). Linguists are interested in the different ways directives are delivered. When a directive is in the imperative form, or other very obvious forms, we call them bald or on-record (ex. “Open the window.”). We can also mitigate directives — this is where the force of the directive is softened or made more polite by changing the syntax of the sentence (“Could you open the window?”), adding politeness markers (“Open the window just a little bit if you don’t mind, dear.”), or hinting rather than commanding (“Gee, it’s stuffy in here, isn’t it?”). On the other hand, we may occasionally aggravate directives, increasing their force through threats or insults (“Open the window or else, idiot!”).

Studies tend to be interested in how princesses look and act; but how they talk is arguably just as important for the gender roles they represent.

In language and gender scholarship, men in many situations tend to use significantly more on-record and aggravated directives than do women. Conversely, if everything else is equal, women tend to mitigate more of their directives than men. These findings tend to be heavily contextual, suggesting that gender performance through language is fluid and changing. Interestingly, it’s also been shown that people think that women mitigate more than men, regardless of the context; this is to the point where real-life women are being encouraged to change their speech in professional environments to be more “assertive” (there’s even an app for that).

I wanted to see if Disney Princess movies had a relationship between gender and directive use that reflected, or reproduced, the differences (real or perceived) found in real life. I collected every directive given in the 12-movie canon (about 2,300 instances in total) and sorted them into the three categories described above for analysis.

What did you find?

The initial finding that a lot of people tend to find surprising is the general ratios of speech: leaving aside any specific linguistic pattern, men just tend to speak a lot more than women do in Disney movies. For more on this, check out this article.

We also found that gender does have a significant effect on the use of directives in Disney movies. Generally, if a directive is issued by a woman, it is more likely to be mitigated (that is, made more polite or softened in some way) than if it is issued by a man. Of course, this is by no means the only factor that influences directive forms; power, for example, plays a much bigger role. A queen speaking to her subjects is much more likely to say, “Silence, fools!” than a male servant speaking to a queen. The urgency of the situation is also important — if someone’s life is in danger, most characters abandon politeness strategies immediately. Nobody says, “Excuse me, but would you mind saving my life?” Although urgency and power have major roles in directive formation, the gender difference holds even when taking those factors into account.

What do your findings mean, in terms of how these messages affect our perception of gender roles? Why is this research important?

As with any quantitative data, it’s hard to say with absolute certainty what any statistical significance “means.” That being said, I would posit that directives are playing a role in how the differences between men and women are portrayed in the world of Disney. And thanks to these numbers, we can quantitatively say what many have been suggesting qualitatively for years: that women in Disney movies are associated with powerlessness, politeness and non-agency compared to their male counterparts.

This doesn’t necessarily change our previous understanding of gender roles in Disney movies. It does, however, lend a quantitative voice to the decades-long debate about the status of princesses as “role models.” And, importantly (at least to me), it adds language into the debate. We in the Department of English recognize that words are of utmost importance; they constitute the form and function of our communication with each other; they are one of the mediums through which we fundamentally construct our identities. Despite this, language is often left out of otherwise comprehensive debates about fair representation and social justice. My hope is that this project and others like it can prove to the general public that linguistics has an important role in our national discourse about gender and equity.

- Categories: